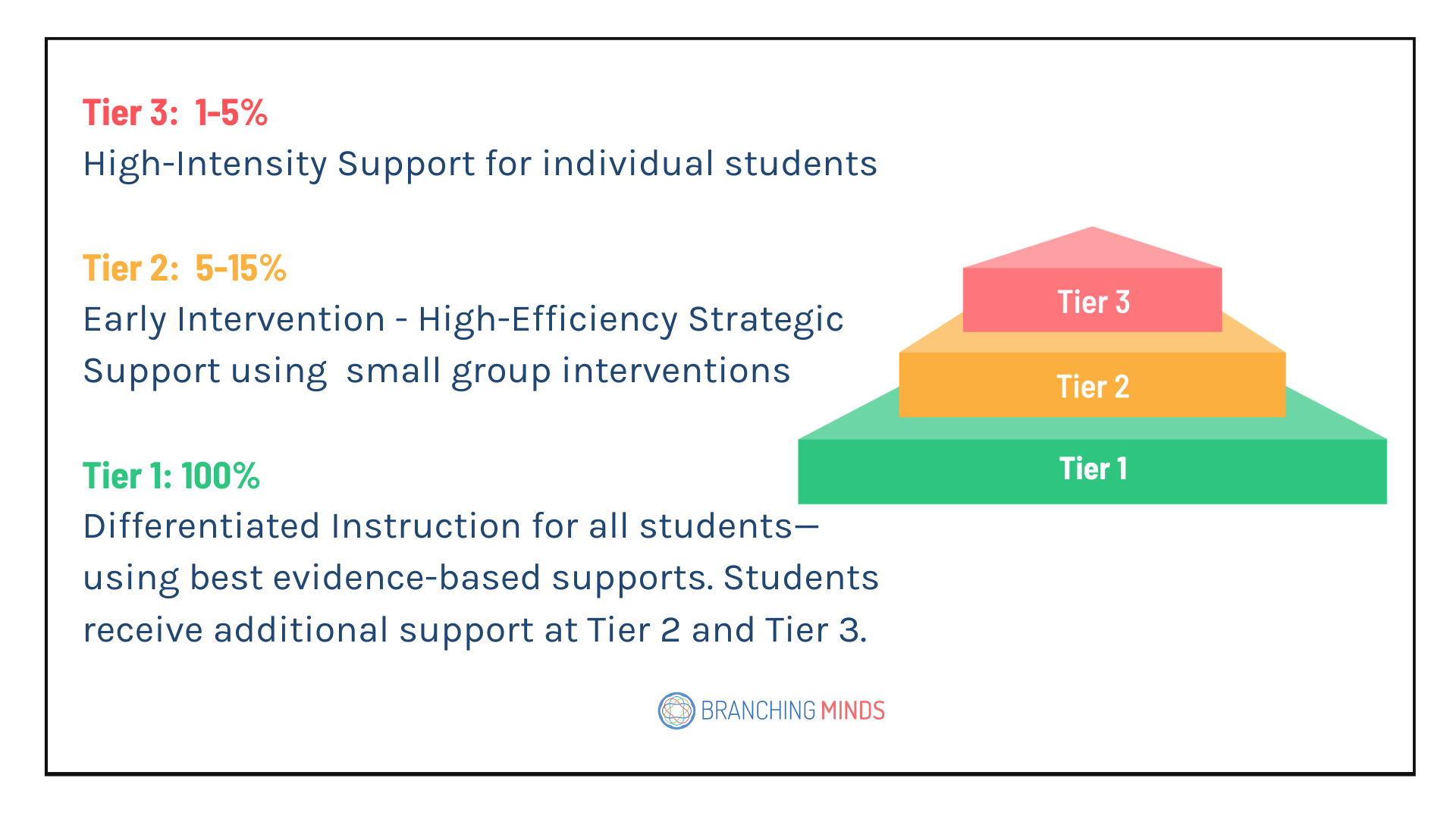

Student goal setting is a topic that is often covered during teacher professional development and in-service days. Educators have naturally been setting goals for students since the beginning of teaching, and goal-setting today has become a critical element of an effective MTSS (Multi-Tiered System of Supports) framework. MTSS meets all students' needs with three levels of support for each school's entire student body.

SMART Goals in MTSS: Key Takeaways

- SMART goals must focus on a specific skill, not just broad outcomes, to guide instruction and intervention.

- Measurement matters. Goals should clearly state how progress will be monitored and evaluated.

- Well-written SMART goals drive better MTSS decisions, leading to more targeted support and stronger student growth.

Within MTSS, Tier I (also known as whole class core instruction), the core curriculum should be meeting the needs of at least 80% of all students. Tier II includes whole class core instruction, with targeted instruction for students needing support, often provided in small groups. Tier III is whole class core instruction, additional targeted instruction, and explicit intensive intervention. Support activities provided to students receiving Tier II and Tier III instruction should be robust, research-driven, and align to students' specific needs.

The MTSS framework hinges upon the use of goals so teachers can measure how students are responding to core and targeted instruction, as well as intensive intervention support. As universal screening and progress monitoring data are regularly evaluated and student performance is considered, goals are set and monitored around a skill the student is working to master. Becky and Dr. Richard Dufour (my childhood superintendent!) popularized the use of SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Results-Oriented, Time-bound) goals in education during their work with schools around the country (DuFour, DuFour, Eaker, & Many, 2006). Using SMART goals within the MTSS framework elevates the goal-setting process, and teachers can engage students into their own learning, create accountability, focus on growth, and connect support directly to specific areas of need.

Over the years, SMART goals have become one of education’s most used acronyms, and also one of the most misapplied. The SMART goal-setting process is powerful, but it can sometimes go awry if the SMART acronym intent is not adhered to when creating the goal. This misapplication results in missed outcomes, especially when applied to MTSS and creating targeted instruction and intervention goals for students. Although you may be thinking to yourself right now, “Oh, no! Not another blog about SMART Goals!” rest assured, this blog is not the standard discussion of what the acronym means. Instead, this article will discuss the common mistakes that are made when creating goals, and how to remedy these errors by effectively creating SMART goals that can be linked to specific student needs within the MTSS framework.

Related resource: Step-By-Step MTSS Intervention Planning With Branching Minds

Mistake #1: The Goal is Not Written Specifically Enough

Mistake Example #1: Matthew will improve reading.

When goals are too broad, it is difficult to select the just-right intervention to support an identified need if the specific skill to receive support is not named. As a result, working towards trying to achieve the goal becomes overwhelming as teachers may not have the alignment between the support they are providing and the goal.

- SMART Goal Remedy: Ensure the goal is specific--it should include a specific skill and a targeted outcome.

- SMART Goal Example: Matthew will orally read a grade level passage at 70 words per minute with accuracy and 3 or fewer miscues as measured by mCLASS: TRC, administered by the interventionist by March 15.

In the SMART goal above, Matthew is working on increasing his fluency and reducing miscues. Specifically, stating this information in the goal allows for Matthew’s teacher to select a support or activity that directly matches his oral fluency need (such as using a fluency letter wheel or creating fluency mini-cards) during intervention time with Matthew.

Mistake #2: The Goal Does Not Lend Itself to Measuring or Tracking Progress

Mistake Example #2: The First Grade Math Targeted Instruction Group will be able to compare and order whole numbers using the symbols < and >.

The mistake example inadvertently creates difficulty in determining if the students in the First Grade Math Targeted Instruction Group are making progress after receiving support.

- SMART Goal Remedy: Establish measurable outcomes for the goal so you are able to determine if the students are making progress or are needing additional support.

- SMART Goal Example: The First Grade Math Targeted Instruction Group will be able to compare and order whole numbers up to 100,000 and represent comparisons using the symbols < and > as measured by aimswebPlus Math with a goal score of 90, administered by the classroom teacher by March 9.

Measurable goals allow for measuring progress. This is critical as teachers work to determine if an activity or intervention provided is making an impact. In addition, measuring progress allows for students to invest in their own learning experience. Research shows that tracking progress towards goals contributes to positive emotions, strong motivation, and could help to spiral the group’s productivity upward. (Yang, Stamatogiannakis, Chattopadhyay, & Chakravarti, 2021).

Mistake #3: The Goal Gets a Bar That is too Difficult to Meet

Mistake Example #3: Brianna will complete two digit into four digit division with no errors, as measured by the interventionist.

The mistake example does not have a realistic outcome as it states that Brianna should master a concept without making any errors. Furthermore, it is important to check to make sure that resources are available to measure progress as stated in the goal, or determine if additional resources are needed.

- SMART Goal Remedy: Make certain the goal you set for a student is attainable.

- SMART Goal Example: Brianna will be able to complete 2 digit into 4 digit division as measured by Aimsweb - Math Computation (M-COMP) with a goal score of 80, administered by the interventionist by March 1.

Brianna’s remedy goal is now realistic for her to achieve, and her teacher is able to select the just-right intervention to support working towards 2 digit into 4 digit division, as well as clearly track her progress.

Mistake #4: The Goal Does not Define Specific Desired Outcomes or Results

Mistake Example #4: Rebecca will remain engaged during remote learning.

In the mistake example, there is no clarity around what behaviors or actions Rebecca will need to complete to accomplish her goal.

- SMART Goal Remedy: Goals should be results-oriented with clear expected outcomes.

- SMART Goal Example: Rebecca will login to Google Classroom on time, keep her camera on during instructional periods, and complete a daily behavior exit ticket at the end of the day 4 out of 5 days each week, as charted at the end of each day by the classroom teacher.

In the SMART goal example, Rebecca has straightforward expectations for her to follow and the desired results are clearly stated.

Mistake #5: The Goal is Not Time-bound

Mistake Example #5: Carlos will be able to increase his phonemic awareness by mastering his CVCs, as measured by the classroom teacher with a goal score of 80 on the EasyCBM Lite - Phoneme Segmenting.

This goal does not contain a time frame when the goal should be accomplished. As a result, it will be difficult to determine if progress is being made and if the targeted instruction Carlos receives has been impactful.

- SMART Goal Remedy: Ensure the goal is time-bound and contains a statement about when it should be accomplished.

- SMART Goal Example: Carlos will be able to increase his phonemic awareness by mastering his CVCs, as measured by the classroom teacher by March 15 with a goal score of 80 on the EasyCBM Lite - Phoneme Segmenting.

The goal is time-bound and includes a time frame in which Carlos’s progress will be measured towards his goal. This goal also specifically states the skill so his teacher can provide targeted support activities to support mastery with CVCs.

Goal Mistakes and SMART Goal Remedy

Finding robust instructional support and intervention activities that align with students' goals is a critical component of the MTSS framework, and it relies on well-created SMART goals for targeted instruction and intensive intervention. Revisiting how goals are created in your building to ensure they are SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, result-oriented and time-bound) will result in student progress, increased student motivation, and impactful instruction.

Related resource: What are SMART Goals?

References

- DuFour, R., DuFour, R, Eaker, R., & Many, T. (2006). Learning by doing: A handbook for professional learning communities at work. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree

- Yang, H., Stamatogiannakis, A., Chattopadhyay, A., & Chakravarti, D. (2021, February 23). Why we set unattainable goals. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://hbr.org/2021/01/why-we-set-unattainable-goals

![[Guest Author] Deanne Rotfeld Levy, M.A.T.-avatar](https://www.branchingminds.com/hs-fs/hubfs/Team/Deanne%2070x70.png?width=82&height=82&name=Deanne%2070x70.png)

About the author

[Guest Author] Deanne Rotfeld Levy, M.A.T.

Deanne Rotfeld Levy is a consultant for Branching Minds regarding MTSS best practices. Deanne is also a University Supervisor at the National College of Education at National Louis University. Deanne previously served as Vice President of Customer Success for Discovery Education and was a Chicago Public Schools special education teacher and case manager. Deanne holds a Master of Arts in Teaching Special Education from National Louis University.

Your MTSS Transformation Starts Here

Enhance your MTSS process. Book a Branching Minds demo today.

.png?width=716&height=522&name=Understanding%20Literacy%20Basics%20(Preview).png)